So, I've been thinking a lot about the relationship between history and social science, particularly in terms of methodology as applied epistemology and ontology. This was occasioned by reading Christopher Pollitt's wonderful book Time, Policy, Management.

It's also been occasioned by me reading about Habermas' distinction between the Lifeworld of everyday experience and language and the System of zweckrationalitat. And I've recently started reading Dorothy Smith's 2001 article 'Texts and the ontology of organizations and institutions'.

Now I have to see if I can put these thoughts in order...

One thing that really angers me in social science is badly written social science. By badly written, I mean the sort of clever post-structuralist stuff that is actually hard work to read. I was reminded of this recently when I said to a colleague that I was very impressed they'd actually managed to read Chouliaraki and Fairclough. Their reply was: "parts of it I read and parts of it I understood... or at least think I understood".

I always find this quite ironic, since a lot of this writing is supposed to be empowering and a critique of language and society. Yet it's unreadable. It links to an idea I'll return to below - literacies. As an academic and a social science I have a different literacy to most people. I read academic texts very regularly and can write in this way as well. My academic literacy has changed recently well - being a busy lecturer I now have to be a lot better at skimming and I'm getting there. But the literacy expected of people like Fairclough and Howarth is a literacy I don't have. And I don't think I wish to have.

As far as I've got in Dorothy Smith's article she's made two points I find interesting that link to this. Firstly, that institutions are recreated by text and secondly that social science uses language to abstract institutions to understand them.

On the second point I have to agree. This is what Habermas was getting at with his notion of The System - reifying things to comprehend them when they actually exist in the Lifeworld. On the first point, this is something I keep coming back to as a historian turned social scientist. Whenever social scientists emphasise the importance of language/discourse/text in creating society I just think "no shit, Sherlock". As a historian the past doesn't exist. It only exists as a few shreds of predominantly written evidence you gather together to tell a story of the past. You critically analyse the text - who wrote it and why? And it's implicit that society and culture is discourse. And this isn't a problem. The standard of evidence is that which Habermas suggests is that which exists in the Lifeworld - the power of the persuasive argument and therefore there are very few certainties in history and as Habermas suggests of communicative action in the Lifeworld: 'the typical states are in the gray areas in between'.

And now I'll return to the first point. In developing something as simple as narrative history doesn't reify to the same extent as social science. It specifically tries not too abstract too much from the texts. You're expected to reference your evidence so other historians can see where you have developed it from. History, I think, as an intellectual project is just about focusing on the contrast from the now. I was reminded of this watching the wonderfully game Lucy Worsley on If Walls Could Talk as she explained that until the advent of modern plumbing in the late nineteenth century the very idea of a "bathroom" was entirely alien. This "problematised" the bathroom and hygiene as an idea immediately. It showed it was partial, social constructed and therefore of interest. When I learnt about the history of literacy in early-modern England this did the same for me. The vast majority of people before the eighteenth century were illiterate. Yet because the written word was things like penny ballads, literacy was actually just different. A penny ballad would be bought by a village and the one literate person would sing it to other villagers. If it was especially good it would be kept and become folklore. The reformation and its emphasis on reading the bible to reflect on one's own spirituality made reading the private act it is today. Therefore we shouldn't talk about literacy, but literacies. When it comes to Chouliaraki and Fairclough I'm as illiterate as a seventeenth century farmer.

Social science, being obsessed with the now can only ever achieve this through reifying objects. If it's positivism it abstracts them into theory and statistics. If it's ANT you turn them into "things". If you're into critical discourse analysis then you use a load of post-modern wank badly translated from Foucault and Lauclau to leave your reader baffled.

This has purposefully been a bit of a rant and I know there's lot of holes in my argument and also I'm generalising about history. But it is a rant because I think there's political implications for social science here. As a planner and social scientist I want to make the world better. If what I write is unintelligible to people then how can I do this? This was something I criticised in my research - the reification of social "things" in strategic policy divorced them from the Lifeworld of community activists, therefore there could not be radical democratic engagement. If I'm doing the same, am I not as guilty as the policy-makers I criticise.

The public popularity of good history highlights this. Pretty decent history books from good historians are often in the best-seller lists. Christ, there's even a few TV channels devoted to the subject. Is there a "social-science TV"? No, there's 24 hour news mis-reporting the "now". I think social science can learn a lot from history to reflect on methodology to make it more readable and change the literacy of social science.

Does this make sense?

The personal blog of Dr Peter Matthews, Lecturer in Social Policy, University of Stirling

Thursday, 21 April 2011

Saturday, 16 April 2011

Localism and community involvement

Just read this worrying post about the removal of the duty to consult in England as part of the "bonfire red tape". Now, I can't say I'm a fan of the Scottish duty to involve which is in the community planning section of the Local Government in Scotland Act 2003. An argument I regularly make is because this exists statutory organisations feel they should consult, even if they're not very good at it or the consultation will just lead to anger, resentment and poor decisions. In a modern social democracy, sometimes I think decisions have to be made against consultation because the benefits are either too dispersed, or too long term, to effect decent consultation, no matter how much "community capacity building" you do. I think it's a pretty good maxim of all public policy decisions - the benefits will be dispersed, long-term and benefit quiet people, while the costs will be concentrated, short-term and anger loud people.

But, I'm not against community engagement per se. I know it works really well. I've seen it work really well. In the right circumstances. And I'd rather that duty be there in the Local Government in Scotland Act than not.

Which leads me onto this excellent exposition of the mess of the Localism Bill. He also makes the point that's slipped under the radar a lot, raised by Professor Sir Peter Hall of planning (my hero....), that the act allows private companies(!) to create the neighbourhood development plan messes (in line with national policy which basically says "build anything you like anywhere", so really what's the point). I can almost her Messrs Barratt, Persimmon and Bellway licking their lips getting ready to flounce into disparate urban neighbourhoods (London, I'm looking at you) shiny plan from planning consultants at the ready and before you know it you've got 1,000 executive flats on your doorstep because "your community" asked for them....

As Chris Brown says, thank God we have the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006. It might not be perfect, but the hoo-ha over Third Party Rights to Appeal during the difficult five year birth of the Act means at least community consultation is central to the act. Although, as I said earlier, the concentrated cost and dispersed benefit of new development are always going to make it tricky.

I need to make this blog look nicer. But in the meantime I've a couple of dissertations to mark.

But, I'm not against community engagement per se. I know it works really well. I've seen it work really well. In the right circumstances. And I'd rather that duty be there in the Local Government in Scotland Act than not.

Which leads me onto this excellent exposition of the mess of the Localism Bill. He also makes the point that's slipped under the radar a lot, raised by Professor Sir Peter Hall of planning (my hero....), that the act allows private companies(!) to create the neighbourhood development plan messes (in line with national policy which basically says "build anything you like anywhere", so really what's the point). I can almost her Messrs Barratt, Persimmon and Bellway licking their lips getting ready to flounce into disparate urban neighbourhoods (London, I'm looking at you) shiny plan from planning consultants at the ready and before you know it you've got 1,000 executive flats on your doorstep because "your community" asked for them....

As Chris Brown says, thank God we have the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006. It might not be perfect, but the hoo-ha over Third Party Rights to Appeal during the difficult five year birth of the Act means at least community consultation is central to the act. Although, as I said earlier, the concentrated cost and dispersed benefit of new development are always going to make it tricky.

I need to make this blog look nicer. But in the meantime I've a couple of dissertations to mark.

Thursday, 14 April 2011

My first attempt at a visualisation...

Monday, 11 April 2011

Marine Spatial Planning

I'm getting interested in marine spatial planning - basically the idea that the use of the sea should be planned like the use of land and just left for a market free-for-all. It's a bit trickier than land-use planning as things float in the sea, so you're planning in three dimensions. The sea is also international. The sea is also subject to lots of old ad hoc regulation regimes. But, we're starting to do.

Scotland passed the Marine (Scotland) Act last year which sets up our Marine Spatial Planning system. And they're consulting on the first national Marine Plan now. My first thought was: where's the map? It's a nice survey with some nice vague obejctives, but you're just left with a feeling of "what do they want, where?", which surely planning is all about, even in the sea?

Anyhoo, I've put together a response to the consultation that I'm going to send off. But it has got me thinking about the utter reticence we have for having actual maps in plans in the UK. We're more than happy to write hundreds of pages of policies about where development can go, but scared of actual maps that actually say we want actual things actually here. I know there's a whole literature out there on this that I should read... But the end of it is we have plans that look like this. The best Structure Plan key diagram I ever saw (it might have been in one of the abolished Regional Spatial Strategies, actually) had, instead of housing sites with actual delivery capacities, just had a house with represented how many new homes that area was supposed to have. The bigger the house, the bigger the supposed capacity. Suffice to say, it just meant it looked like a few places were going to get two gigantic houses whereas everywhere else would get a little house each.

Scotland passed the Marine (Scotland) Act last year which sets up our Marine Spatial Planning system. And they're consulting on the first national Marine Plan now. My first thought was: where's the map? It's a nice survey with some nice vague obejctives, but you're just left with a feeling of "what do they want, where?", which surely planning is all about, even in the sea?

Anyhoo, I've put together a response to the consultation that I'm going to send off. But it has got me thinking about the utter reticence we have for having actual maps in plans in the UK. We're more than happy to write hundreds of pages of policies about where development can go, but scared of actual maps that actually say we want actual things actually here. I know there's a whole literature out there on this that I should read... But the end of it is we have plans that look like this. The best Structure Plan key diagram I ever saw (it might have been in one of the abolished Regional Spatial Strategies, actually) had, instead of housing sites with actual delivery capacities, just had a house with represented how many new homes that area was supposed to have. The bigger the house, the bigger the supposed capacity. Suffice to say, it just meant it looked like a few places were going to get two gigantic houses whereas everywhere else would get a little house each.

Friday, 8 April 2011

A proper post for a start...

So, I'm preparing a course on Urban Infrastructure Management for next year which includes classes on urban green space. Writing out what this will cover I realised I had better cover good old fashioned town and country planning - thinking about the relationship between how much grey space we have and how much brown space we have.

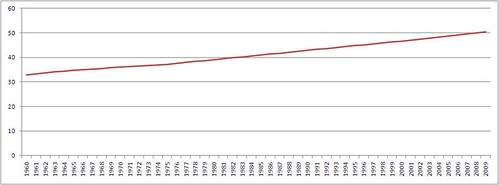

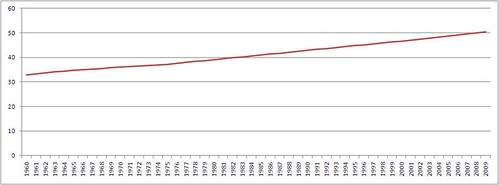

Well, you won't have noticed, but the World Bank recently announced that more than half the world's population now live in urban areas. The UK hit that mark in 1851. I think Scotland hit it at something like 1821 because of the Highland Clearances. Anyway, the graph looks like this:

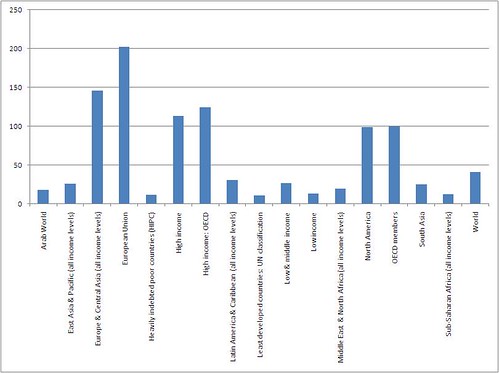

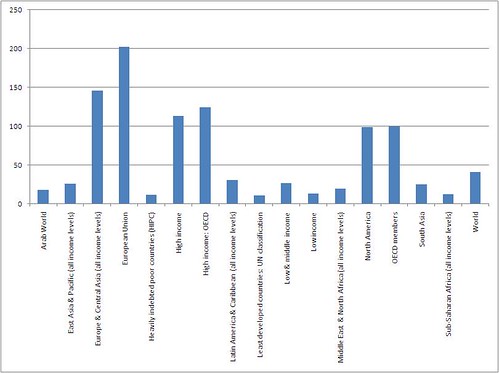

The World Bank has an amazing data site so I downloaded the metadata for the numbers for countries. Extracting from this I produced this graph of percentage change in urban population between 1960 and 2009:

Which is more interesting than the World picture really. If you look at it, most of the urbanising has been happening in those countries that have had the fastest growing economies since 1960. Note the EU urbanizing rate of over 200%. This chimes with what I know of the German Economic Miracle and the "Celtic Tiger" growth of Ireland being driven in great part by agricultural developments freeing up labour to move to cities and provide reasonably cheap, skilled labour.

Which kinda links to what led me to getting this data, the fact that because of the industrialisation of agriculture many of the "brownfield" sites in cities now have greater biodiversity than you get in the countryside. Like the wonderfully named Nob End, near Bolton.

My mate's dad has some wonderful photos of urban biodiversity over on his flickr stream.

Well, you won't have noticed, but the World Bank recently announced that more than half the world's population now live in urban areas. The UK hit that mark in 1851. I think Scotland hit it at something like 1821 because of the Highland Clearances. Anyway, the graph looks like this:

The World Bank has an amazing data site so I downloaded the metadata for the numbers for countries. Extracting from this I produced this graph of percentage change in urban population between 1960 and 2009:

Which is more interesting than the World picture really. If you look at it, most of the urbanising has been happening in those countries that have had the fastest growing economies since 1960. Note the EU urbanizing rate of over 200%. This chimes with what I know of the German Economic Miracle and the "Celtic Tiger" growth of Ireland being driven in great part by agricultural developments freeing up labour to move to cities and provide reasonably cheap, skilled labour.

Which kinda links to what led me to getting this data, the fact that because of the industrialisation of agriculture many of the "brownfield" sites in cities now have greater biodiversity than you get in the countryside. Like the wonderfully named Nob End, near Bolton.

My mate's dad has some wonderful photos of urban biodiversity over on his flickr stream.

Thursday, 7 April 2011

Welcome

Well, I've started a blog (again).

It might be all about planning and governance and stuff.

At the moment, I'm interested in:

This post will probably be copied into my profile section when I have a chance.

It might be all about planning and governance and stuff.

At the moment, I'm interested in:

- spatial equity (why concentrations of affluence exist)

- governance and community participation (carrying out a literature review of middle class community activism as part of the AHRC Connected Communities programme)

- advanced qualitative methodologies

This post will probably be copied into my profile section when I have a chance.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)